Governing the Information Commons

Note: This essay was originally written as a talk for World Information Architecture Day.

Introduction

Before we start the talk, I have a little something for you all. I brought this basket of snacks - mostly candy, though there’s a couple of healthy snacks for those of you who are into being healthy.

So who should get what? How should we decide?

Maybe I should decide. That seems fair, right? After all, I brought the snacks. But what if I decided in a really unfair way? What if I decided to give all the snacks to someone who’d be reviewing my talk later? Or what if I decided only men, or only white people, should get snacks?

What if you learned that I didn’t buy the snacks? What if I got them from the conference organizers and I was told to give them out to everyone? Do I still get to decide what happens to them? What if I stole the snacks from the conference organizers?

What if someone in this room is allergic to all but one of the snacks? Do we have an obligation to give them that snack? What if someone’s allergic to airborn particles in the snacks? Do we have an obligation not to eat at all?

What if there’s an earthquake in this room and we’re stuck in here for hours, or days? Is it still fair for me to decide who gets to eat our only food?

I’m going to pass out the snacks now. I’ll give the basket to the person closest to me, tell them to pick one, and pass it along. That’s what most people do in this situation - the default distribution method, if you will. But the default choice is still a choice. It still has consequences.

Turns out managing resources is more complex than it seems! There’s a whole lot of uncertainty and conflicting needs and frankly, humans don’t do great with uncertainty. It makes most of us pretty anxious. And so we develop concepts and systems to help us manage uncertainty. And one of those concepts we’ve developed is property rights.

What is property?

Property is, approximately, “who can do what with what” and it is a legal and social construct. Property isn’t some naturally occurring thing that’s the same in all places and times. Every culture is different and every culture changes how they conceive of property over time.

Probably the most stark example of that is how, in this country, up until the 1860s, some human beings were considered property. Property rights in this country included the right to own another human being and do whatever you wanted to them. Now thankfully that’s not how our legal system works anymore, but it’s a clear reminder both that property regimes are constructed by law and culture, and that those choices have the deepest possible moral and practical implications.

Another case of property law changing over time is the treatment of women, who in many places in the United States up until the mid 19th century were treated as the property of their husbands, through a system known as coverture. Many women did not have a right to own their own property or money, or even to be guardian to their children if their husbands died. Women have gained rights slowly over time, becoming less and less like property, but even as late as 1993 there were still two states in which men had the legal right to rape their wives.

These kinds of piecemeal changes make clear that property is not a single right that you either have or don’t. Instead, people like to call it a “bundle of sticks”. There’s many rights relating to a single object or resource, and you may have different rights in different contexts.

If I’m an artist, and I sell you my art, you typically get the right to view it and the right to keep others from viewing it, but you don’t have the right to destroy it. And that makes sense, doesn’t it? I likely poured my heart and soul into my art, why would I want it to be destroyed? Our legal system respects that right not to see my work destroyed so much that unless I specifically waive this right when selling it to you, I retain it by default.

Here’s another example, my cat Tybalt. When I adopted her, the rescue organization made me sign a contract that said if I decided I didn’t want her, I’d give her back to them rather than dumping her out on the street or even giving her to somebody else. I own her - inasmuch as a human can ever own a cat - but the rescue retains some rights to her.

A third example: rivers. Did you know that many rivers in the United States are public property? It depends on if they’re “navigable”, which is a term of some contention, but essentially if they can be navigated they belong to the public. The government doesn’t even have the right to privatize them, like they can with some things they own, because the rivers are considered held in trust by the government for the public. So if you buy land that a navigable river runs through? You can’t stop people from going through it on the river.

Okay, so how many of you knew about these laws regarding what you can do with art, or pets, or rivers? How many of you knew about all three?

We mostly don’t know about these kinds of distinctions, even though they’re quite common. We just think, you know, there’s public property, and there’s private property, and if it’s your private property you can do whatever you want. It’s yours! You own it! Do whatever with it! You do you.

And this isn’t always a problem. Sometimes the situation is that simple. But often it’s more complex and if we need to balance competing needs, sticking with this oversimplification will cause us so many problems.

And this, I think, is at the heart of the problem that so many social media platforms are having. They’ve adapted this oversimplified conception of private property and now they don’t know how to handle conflicting needs.

How digital platforms encode concepts of private property

What do I mean by saying social media platforms have adapted or encoded concepts of private property in their platforms? Well, who owns these tweets?

As with physical property, the right to a digital resource like a tweet or a thread of tweets is not one right but a bundle of rights - the right to view, like, reply, share, report, delete. And these rights are instantiated in the code.

For those of you who aren’t familiar with programming, a very simplified version of a piece of Twitter’s code base might look something like this:

def can_view(tweet, potential_viewer):

show_to_viewer = True

if tweet.privacy_status is "private":

show_to_viewer = False

if potential_viewer.status is "blocked":

show_to_viewer = False

if tweet.number_of_retweets > 1000 and tweet.no_viral is True:

show_to_viewer = False`

Through these “if statements”, Twitter controls access to resources. Sometimes they let users change elements, so that a user might say “this person is blocked” or “this person is not blocked”. But Twitter itself sets the scope of what rights can be exercised.

That means that there are rights which aren’t instantiated in the code, which no one gets to exercise. For instance, the last if statement in the psuedocode gives the user the right to prevent their tweet from going viral. Once there’s a thousand retweets, no one else can see it. Twitter could even let each user set a custom number of maximum retweets, so that each person could operate within their own comfort level. Now, Twitter doesn’t do this, but that’s a design decision on their part. By not adding that code, they’ve decided that no one gets access to that right.

The oversimplified conception of private property adopted by digital platforms has three parts. We’ll go through them in the context of Twitter, although we will be talking about other platforms soon.

1. Everything has a single owner.

Each tweet in this thread has a single owner. Of course some accounts are owned by corporations or groups, but importantly, the platform itself does not facilitate that. Instead, groups using singular accounts must figure out for themselves who controls the account.

Not coincidentally, this works out best for corporations, which have a whole legal and financial structure that can enforce their singular control over the account. That’s a big part of why corporations even exist - to let groups of people act as though they are a singular person. That’s why you sometimes hear corporations called “legal persons”. Because of this corporate structure, if, say, an employee posts spam to the account they can be fired, because the account doesn’t belong to them, it belongs to the legal person of the corporation.

Conversely, I know of a number of informal, non-hierarchical groups that have had great conflict over who has access to Twitter accounts. They don’t have the legal structure to determine access, and Twitter isn’t providing a structure to share access either.

Now Twitter does have a not super well know way to share accounts called Teams, where you can share posting access to your account with others without having to give them your password. But crucially, there’s still a singular owner of the account that’s being shared, and they can revoke that access at any time. So any group that doesn’t have one singular leader who is trusted by everyone else is still kinda screwed.

2. The owner has all rights, and everyone else has a subset.

If I posted a tweet, you can reply to it, like it, or retweet it. I can do all of those things, but I can also delete the tweet and block you from seeing it. Your rights are a subset of mine. There’s no right regarding my tweet that you have that I don’t.

3. The owner’s rights trump everyone else’s.

The obvious example here is the case where someone tweets something abusive - they’re causing harm, but they have a right to say what they want in “their” tweets. Twitter does sometimes intervene in cases of abuse, but they’ve always been very resistant to doing so, and often have had to be pushed. Also, when they intervene, they don’t do so through the “normal interface”, so to speak - they go in through the back end, using features not availability to most people. Handling abuse is exceptional and outside the system.

Another example of where rights conflict is the right of the user to delete their tweets. There’s a strong argument to be made that the right of citizens to access public speech means that politicians and public figures shouldn’t be able to delete their tweets. But Twitter has historically resisted this. In fact, they’ve gone out of their way to protect this right to delete. The Sunlight Foundation used to run an account called Politwoops which republished tweets from elected officials that had been deleted, but Twitter shut down those accounts for violating their terms of service. After months of outrage from the community they did reverse the decision, and ProPublica now hosts Politwoops, but Twitter had to be really pushed.

A final example is well-publicized case of Trump blocking people from following him on Twitter. Courts ruled that citizens had a right to follow their President on Twitter and see his communications, and ruled that Trump had to unblock people. But note that there wasn’t any recourse in this case through Twitter. The platform itself can’t handle these conflicting needs and if Trump started blocking people again he’d have to be sued again - as far as I know, Twitter itself hasn’t had to change anything about its platform in response to the case. Again, this is a conflict being handled outside the system because Twitter’s default is that the individual owner’s rights trump everything, no pun intended.

We see this pattern across many platforms, not just Twitter.

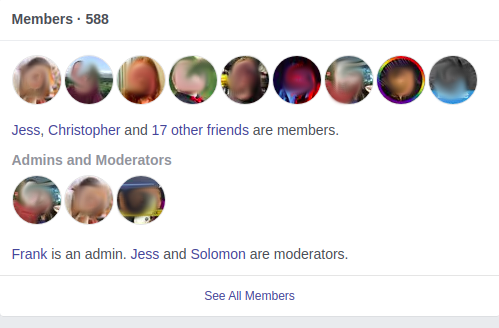

Facebook posts have a single owner, and so do groups. (You can’t actually see who the owner is, even when you’re the owner. I have a few Facebook groups and I looked through them, but I couldn’t find anywhere which said so. According to the documentation, though, it has to be one of the admins. So in this group we know the owner is the one administrator.)

Owners of Facebook groups can delegate some authority to administrators and moderators, but they still have ultimate control and can remove those administrators and moderators on a whim.

Facebook gives individuals much more nuanced controls over who can see their posts than Twitter does, but it’s still very much abiding by the principle of ‘your posts, your property’.

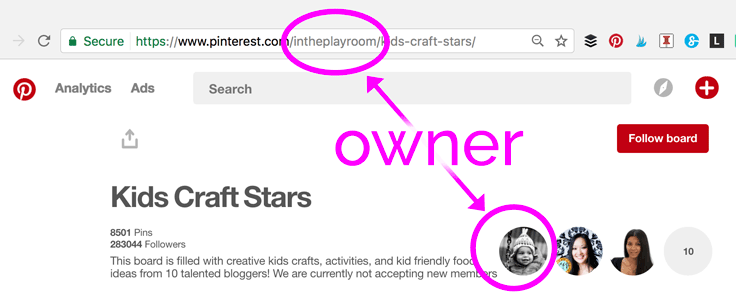

Pinterest again has posts which belong to a single owner. They also have group boards which again belong to a single owner, and in Pinterest’s case you can’t even transfer ownership to someone else.

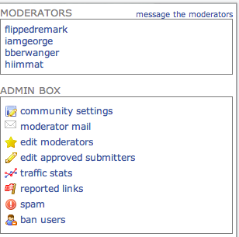

Reddit has subreddits, which are a lot like Facebook groups. In fact, I suspect that Facebook has copied some of the features that Reddit provides. There are ways in which subreddits are better than Facebook groups and provide more flexibility and customizability to their communities, but they still operate under this “one owner” rule, where the oldest moderator - the one whose been moderating the longest - has the right to remove all other moderators. Conversely, newer moderators have no right to remove anyone older than them.

So even in a case where there’s a lot of thoughts going into how to improve communities and community interactions, you still have this unquestioning assumption of a singular owner who can do whatever they want with a group.

Mastodon and the Fediverse

Mastodon and other “fediverse” projects go beyond challenging assumptions about community norms to challenging assumptions about ownership and control. Mastodon is a decentralized, open source social media platform. It was created by people who expressly dislike the idea that companies like Facebook and Twitter have control of their relationships. Instead, these platforms work by having decentralized or “federated” instances, hence the nickname “fediverse”.

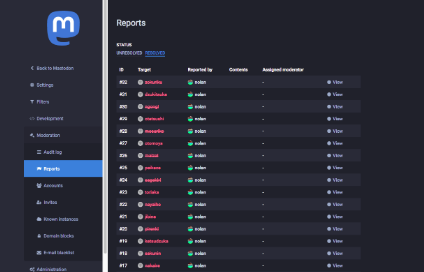

But even here, the individual instances have, once again, a single owner, called an administrator. If you want to control your own experience you have to run your own instance, but the vast majority of people don’t have the time or the knowledge or the resources to do so. Users with abusive administrators don’t have any recourse except to switch instances. Furthermore, because the model is one of individual ownership instead of collective governance, there’s few tools to address collective problems like abuse.

To be clear: Mastodon and other Fediverse projects are operating on a shoestring budget compared to billion dollar companies like Facebook. Perhaps they’d like facilitate collective governance but don’t have the resources to do so. I don’t mention them here to criticize them or say they ought to be doing better. I bring them up to make the point that these norms around ownership are so taken for granted that even projects expressly devoted to empowering users by wrestling ownership and control from big companies still encode these norms.

These norms are failing us

Once you start seeing this pattern in digital platforms, you see it everywhere. But what are the consequences of the unquestioning adoption of these norms?

Well, I think we can all agree that social media platforms are having some problems. These problems are not just caused by their ownership paradigms, obviously, but I’d argue that all are exacerbated by them. Misinformation and disinformation, harrassment and bullying, hate speech and incitement to violence, stolen content spreading everywhere and fair use content getting unfairly taken down, spam.

These are all social harms and platforms don’t have the conceptual tools to think about collective mitigation of those harms, let alone the technical tools to enable collective mitigation of them. And that’s because they’re locked into a property model where ownership is absolute and cannot be compromised regardless of the harm being caused.

Platforms themselves are not ignorant of these problems I’ve listed. I’m sure that many of the people involved are deeply distressed by them and worried by how difficult they seem to solve.

One company’s solution to the problem of abuse is especially interesting.

Facebook has been so besieged by criticisms of how they handle content moderation decisions that they’re creating something called the ‘Facebook Supreme Court’. This is meant to be a legally distinct organization from Facebook that has the power to review and overturn moderation decisions.

I find the framing here fascinating. Facebook has been using a private property model on their platform, but when it’s clear that that’s not working, what do they turn to? Public property. They use language invoking the most authoritative body of one of our three branches of government.

But government owned property and privately owned property are not our only two conceptual options. There are many other approaches we could use, and I favor one in particular: commons management.

Governing the Commons

No one person invented the practice of commons management, but one of the leading lights in researching and understanding it was Elinor Ostrom, who won a Nobel Prize for her work in 2009.

Ostrom wrote a book called Governing the Commons, in which she looks at a bunch of different commons resources, which run the gamut from Swiss meadows and forests that have been managed as a commons continuously for nearly a thousand years to the efforts to manage twentieth century California water reserves. She found that the commons that survived and thrived tended to abide by certain principles, and those that struggled did not.

I’m going to go through these eight principles one by one, and we’ll talk about how to apply each one to social media platforms, which are after all a bit different from, say, a Swiss meadow.

1. Clearly defined boundaries should be in place.

By definition, it is difficult to exclude people from benefiting from a commons. But difficult doesn’t mean impossible - in fact, drawing boundaries is essential towards governing a commons. They need to be drawn communally because nature won’t do it for you.

In the case of a social media website, there are several different boundaries we might draw. We might say that public posts are part of the commons, but private posts are not. We might say that all posts and all comments are part of the commons, or that something becomes part of the commons only when a sufficient number of people view it, or comment on it, or share it.

2. Rules in use are well matched to local needs and conditions

The rules that govern a commons must be well matched to that particular commons. Rules to govern a lake aren’t going to be the same as rules to govern a river - and you’ll have different rules for each lake based on who’s using it and what they’re using it for. Everything needs to be adapted to the context.

The same goes for a social media commons. If you try to make rules that work everywhere, they’ll work nowhere. Rules that are okay for, say, San Francisco, might be deadly in Myanmar.

3. Individuals affected by these rules can usually participate in modifying the rules.

Rule three follows on rule two. How can you create rules that are well matched to local needs without letting local people create and modify the rules? After all, the people most informed about the consequences of a rule are the people who have to bear those consequences.

I often see people making suggestions for how to make platforms better. Even if people are just complaining, I bet most complainers if actually engaged and prompted about their problems could come up with good suggestions for changes.

But modern platforms aren’t run like this. Instead people typically complain to a support form. These complaints are, if you’re lucky, aggregated and made available to the product management team, which decides what issues they want to fix and how. The changes are tested on users, usually not the same users who complained and sometimes not in a way where the users even realized they’re being tested. This change-and-test cycle happens over and over again until the product team is satisfied, at which point the changes will roll out to everyone.

There are some platforms who do better than this. But there are many that do worse. Some don’t even have a way to suggest changes to the system - for instance, have you ever tried making a feature request or even asked for help from Google? You get crickets, unless you’re a paying customer.

4. Monitors, who actively audit behavior, are accountable to the people whose behavior they’re auditing.

I call this the “who watches the watchmen” principle. Monitoring is a type of power, and you need accountability so they don’t abuse their power. And this is maybe the biggest problem with social media sites - the lack of accountability of the monitors.

Facebook’s Supreme Court is an attempt to address just this issue, the lack of accountability of their moderation system. But notice that they’re not trying to fix the system itself, they’re trying to create an external check on it.

And Facebook’s system is particularly terrible, because not only are monitors unaccountable to the people they’re monitoring, they are themselves strictly policed, low-wage works who develop PTSD from their monitoring work. So not only are they unaccountable to the people they’re monitoring, even when they are able to empathize with users and advocate for positive changes to the system, they have no power to do so within Facebook. It’s the worst of all worlds.

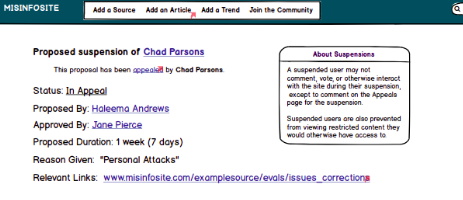

5. People who violate operational rules are likely to be assessed graduated sanctions, depending on the seriousness and context of the offense.

People violate rules for different reasons. Some are trying to be jerks. Some didn’t even know about the rules. It’s important to be sanctioned or punished based on context.

Ostrom writes about how the Japanese village of Yamanake responded during the Great Depression of the 1930s:

“Almost all the villagers knew that almost all the other villagers were breaking the rules: sneaking around the commons at night, cutting trees that were larger than the allowed size, even using wood-cutting tools that were not permitted. This is precisely the behavior that could get a tragedy of the commons started, but it did not happen in Yamanaka. Instead of regarding the general breakdown of rules as an opportunity to become full-time free riders and cast caution to the winds, the violators themselves tried co exercise self·discipline out of deference to the preservation of the commons, and stole from the commons only out of desperation. Inspectors or other witnesses who saw violations maintained silence out of symptahy for the violators’ desperation and out of confidence that the problem was temporary and could not really hurt the commons.”

The social media giants are actually not terrible at graduated sanctions - most sites do a combination of warnings and suspensions and bans - but without transparency and accountability for how these sanctions are applied,the fact that they’re graduated is not super helpful on its own, because there’s still suspicion about why one person deserved this sanction in this context or that sanction in that context.

6. Appropriators and their officials have rapid access to low-cost local arenas to resolve conflicts among appropriators or between appropriators and officials.

If you don’t give people a quick way to resolve conflicts, the issues will boil up until they boil over. They’ll cause a lot more resentment and damage that way. So providing this kind of access is key, so that frustration can be addressed early on,and the social bonds that we all rely on can be maintained. That arena for conflict resolution can also serve as a way of proactively identifying that maybe there are rules that need to be changed.

7. The rights of appropriators to devise their own institutions are not challenged by external authorities.

In the case of the commons that Ostrom was studying, external authorities often meant governments. Many a commons has been destroyed by a government stepping in and enforcing their own rules at the cost of the rules agreed upon by the members of the commons.

In the case of social media platforms, these authorities are less likely to be the government, and more likely to be the platforms themselves. Because they control the platform, they control what kind of rules can be devised.

Some users try to subvert the control of the platforms through browser add ons and third party sites such as TweetDeck or Tumblr Savior. But platforms will often make changes to the site which break these changes, intentionally or uninentionally, and even if they don’t there’s a limit to what these sites can change.

8. Appropriation, provision, monitoring, enforcement, conflict resolution, and governance activities are organized in multiple layers of nested enterprises.

As I’ve said, one size doesn’t fit all. We need to adapt our rules to local circumstances. So what does that mean on a platform with a billion users? Well, most likely that means we want not one enormous commons but many nested commons, so that different corners of the platform can design their own systems.

And platforms do make these local distinctions when forced. For instance, Facebook is much better about removing far-right hate speech from German Facebook because the German legal system requires it.

What a commons platform looks like

I’ve spent a lot of time talking about Twitter and Facebook and other platforms that use this oversimplified private property model. But what does a platform that embraces the idea of a digital commons look like?

Let’s talk about Wikipedia! It’s not really a social platform in the way that Twitter or Facebook is, but it has some structural similarities and of course it is the only major website that truly operates as something like a commons.

Yes, Wikipedia has problems. (You can learn about some of these problems by going to the Wikpedia page Criticism of Wikipedia.) But overall I’d say it’s largely successful.

Its goal is to be the world’s encyclopedia and it has been since 2007 when it reached 2 million English language articles. It now has 50 million articles in 285 languages.

It’s widely used - depending on how you define visits, it’s one of the most commonly visited sites on the web.

And it’s relatively reliable. Wikipedia bills itself as a “first word” on each subject, rather than the last word, but studies have found it compares well in terms of reliability to traditional encyclopedias and even domain-specific texts and reference materials.

So how is Wikipedia a commons? Let’s go through our eight principles.

1. Clearly defined boundaries should be in place.

If you know one thing about Wikipedia, it’s this - that anyone can edit it. That’s hardly a clearly defined boundary, is it? But Wikipedia actually has complex policies and multiple tools to deal with the abuse and spam that inevitably arises from their “anyone can edit” rule. For instance, when someone is spamming a page, and if they don’t stop when warned, they can be blocked from editing. When multiple spammers are trying to edit the same page, or if there’s an “edit war” going on, where people disagree on what the page content should be and are going back and forth, the page can be “protected” so that only registered users can edit.

So there are boundaries here, and the Wikipedia community has thought carefully about how to balance the benefits of openness with the labor involved in repairing the harm caused by bad actors.

2. Rules in use are well matched to local needs and conditions

In an analysis of the Featured Article process by Viegas, Wattenburg and McKeon, the authors found that Wikipedians adapted their rules to handle Featured Articles specifically - a featured article is one that is linked from the front page. They write that “originally, FA criteria did not require references and citations explicitly. Now, the standard FA must have inline citations and a comprehensive coverage of its subject matter.”

Another example, pointed out by Noack, Weinhardt and Dreier, is that Wikipedia pages that outline Wikipedia policy cannot be edited by random users.

3. Individuals affected by these rules can usually participate in modifying the rules.

Wikipedia really excels here: the vast majority of their rules and policies were created by the community through a collaborative process. Anyone can submit proposals to change policy and the community discusses the proposals multiple places.

You can also check out failed past proposals and summaries of perennial proposals. The language used in introducing the Perennial Proposals page exemplifies the nuanced approach Wikipedia takes to community rulemaking: “It should be noted that merely listing something on this page does not mean it will never happen, but that it has been discussed before and never met consensus. Consensus can change, and some proposals that remained on this page for a long time have finally been proposed in a way that reached consensus, but you should address rebuttals raised in the past if you make a proposal along these lines.”

4. Monitors, who actively audit behavior, are accountable to the people whose behavior they’re auditing.

This is another area in which Wikipedia is a role model.

Community Self-Monitoring

Wikipedia’s structure facilitates community self-monitoring. All users can “add, revert, delete article content, or flag articles for possible deletion; they may file and participate in reports for misconduct and misuse of editing tools, and in some cases they may close discussions and deletion debates. They may even issue official user warnings to other editors.” Importantly, the people who care most about each page’s success are the ones who pay closest attention to it, and so users end up monitoring each other.

Ostrom talks about how important such a setup can be. She writes about irrigation systems (emphasis mine):

“Irrigation rotation systems, for example, usually place the two actors most concerned with cheating in direct contact with one another. The irrigator who nears the end of a rotation turn would like to extend the time of his turn (and thus the amount of water obtained). The next irrigator in the rotation system waits nearby for him to finish, and would even like to start early. The presence of the first irrigator deters the second from an early start, the presence of the second irrigator deters the first from a late ending. Neither has to invest additional resources in monitoring activities. Monitoring is a by-product of their own strong motivations to use their water rotation turns to the fullest extent. The fishing-site rotation system used in Alanya has the same characteristic that cheaters can be observed at low cost by those who most want to deter cheaters at that particular time and location.”

Moderator Accountability

Now, Wikipedia does have monitors with special powers. As they put it: “Only administrators may physically delete entire articles, protect articles from improper editing and disruption, and block users”. But these administrators are clearly accountable to editors.

First, every action they take is logged publically, which means they can be audited by the people they’re auditing. Second, their decisions or behaviors can be questioned via Wikipedia’s usual dispute resolution procedure (which we’ll talk about in a minute, when we get to principle 6). And third, if those dispute resolutions fail, they can be brought to the Arbitration Committee, which is a group of volunteers elected by the community at large, and if the Arbitration Committee thinks its necessary, the administrators can be sanctioned or stripped of their position.

5. People who violate operational rules are likely to be assessed graduated sanctions, depending on the seriousness and context of the offense.

Once again, this is something Wikipedia does well. Take the example of responding to user vandalism. The community provides templates for ten different kinds of warnings you might give to a suspected vandal.

When blocking users, again one is encouraged to use a type of block appropriate to the circumstances. Blocks can be made for different lengths of time, they can prevent the user from editing a specific page, or their own “profile” page, or all of Wikipedia, they can prevent a user from sending email through the site, or it can prevent anyone from a given IP address from creating new accounts.

6. Appropriators and their officials have rapid access to low-cost local arenas to resolve conflicts among appropriators or between appropriators and officials.

If you go to any Wikipedia page, you’ll see a “talk” tab at the very top - clicking this will bring you to the discussion happening behind the scenes about what the page should contain. This can be a low-cost way for people to work out disagreements and there are community norms for trying to resolve issues. There are other dispute resolution mechanisms such as the third opinion page or the Dispute Resolution Notice Board or the requests for comment board, and they all say, before you can use them, you have to try the talk page.

7. The rights of appropriators to devise their own institutions are not challenged by external authorities.

Twitter and Facebook are corporations governed by a board of directors and motivated by profit. They can make moderation decisions by fiat, and to the limited extent that they do allow individuals to make their own decisions, they can overrule them, because they “own” the platform.

Wikipedia, conversely, is run by the Wikimedia Foundation. As a non-profit incorporated in the United States, they have a legal obligation to act in the best interest of the non-profit and not for their own personal enrichment or benefit.

Furthermore, a quarter of Wikimedia’s board is elected by Wikimedians. And so all of this combines to legally reinforce the organizations’s commitment to taking a hands off approach and letting Wikipedians decide for themselves how Wikipedia should work.

8. Appropriation, provision, monitoring, enforcement, conflict resolution, and governance activities are organized in multiple layers of nested enterprises.

It’s not clear to me how much there are nested commons in Wikipedia, although the different language wiki are naturally composed of different communities. There certainly don’t seem to be a formal nested community. But there may be subtleties I’m missing as a relative outsider to the Wikipedia community.

Comparing commons platforms to private property platforms

I haven’t done any sort of rigorous quantitative study that would back my sense that Wikipedia is a healthier site with fewer problems than Twitter or Facebook. And I haven’t found many comparisons in the literature. But I think one recent anecdote may be instructive.

So we’ve got this Coronavirus going around. And misinformation about it has been spreading on social media websites. According to an article in Foreign Policy, here’s how some of the major social media sites we’ve talked about so far are doing:

Facebook has been using its fact-checkers to try to fact-check information that’s shared, and uses that to limit the spread of those particular links and to provide warnings to users. But if you search for coronavirus on Facebook, the two top hits are private groups which spread misinformation. “On joining one of those groups, you may be welcomed by a post asking: Is it true that the United States invented the coronavirus to destroy China’s economy? The top comment: “True.””

On Twitter, some of the most prominent people spreading misinformation have been banned, but not until after their posts were shared tens of thousands of times.

And on Reddit, there are two subreddits devoted to the coronavirus, both with more than 50,000 users. One has been very conscientious about enforcing rules about only using information from reliable sources. but the other has been stoking fears that Coronavirus is a biological weapon made by the government.

How does Wikipedia compare? According to an article in Wired, over 18 million people have read Wikipedia articles related to the outbreak - a number that’s undoubtedly much higher by now - so it’s important they get things right.

Wikipedia has locked the articles so that only users with accounts older than 4 days can edit them, although anyone can still post to the talk page and more established users have identified useful information in the talk pages and incorporated it into the articles.

They’ve also created an article devoted to Coronavirus misinformation, which makes it easier for both editors and readers to be skeptical about misinformation that they see, both elsewhere on Wikipedia and other places online and off.

Has this helped? Hopefully at some point a research group will go back and comprehensively survey the edit history of the relevant pages, but for now, anecdata will have to do. First - I haven’t seen any reports of significant misinformation staying up on Wikipedia for long. I skimmed the edit history for one of the main pages myself, and I had to go back several days and nearly a thousand edits before I found something that looked like misinformation. And it was a relatively minor case - someone cited a fatality rate of 2% without including the caveat that the source thought the rate could be orders of magnitude different.

How damaging is that piece of misinofrmation? Does it compare to Twitter or Facebook? That’s up for you to decide, but to me, I’d prefer to get my information from Wikipedia.

New models, new futures

Hopefully Wikipedia’s success has made you at least curious about the possibilities of incorporating commons governance into social media platforms and maybe other areas of digital life - or even offline life.

What would Twitter, Facebook, or Reddit look like if they were more like a commons?

Of the three, Reddit’s probably the closest to a commons. What if they changed their moderation structure so that instead of the oldest moderator being the owner, the moderators operated by consensus or majority vote? What if they had the membership of the group select an owner?

Or, conversely, Twitter is the least like a commons - but they can still make commons-like changes. They could make their moderation system more transparent and accountable, so that users could better understand what rules were being enforced and why.

On Twitter, individuals can import block lists, taking advantage of other peoples’ knowledge about bad actors. But these lists are created externally to Twitter, so they’re hard to share, and there’s no real accountability regarding who gets added to the blocklists. Twitter could provide tools for users to collectively manage these blocklists.

Facebook, like Reddit, could change how its groups are owned, allowing for multiple owners or for communities to own themselves. Like Twitter, they could facilitate the collective management of block lists.

But of course we don’t have to wait for the big social media platforms. We can create new social worlds ourselves.

The Glizzan Project: a new model for platform governance

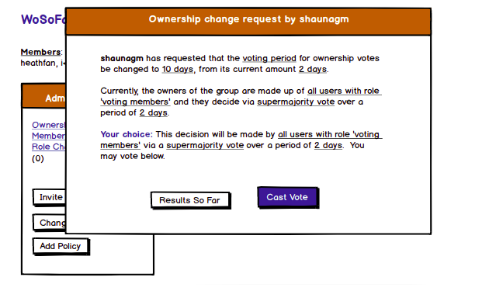

I’ve been exploring one avenue for doing this, by building a programming library that allows people to build complex governance structures, including commons-style structures.

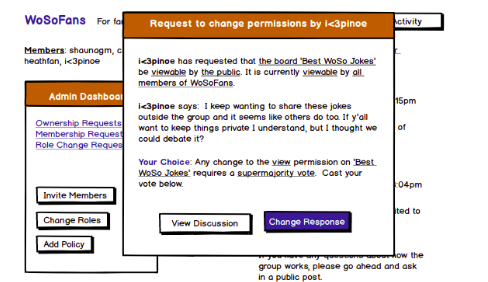

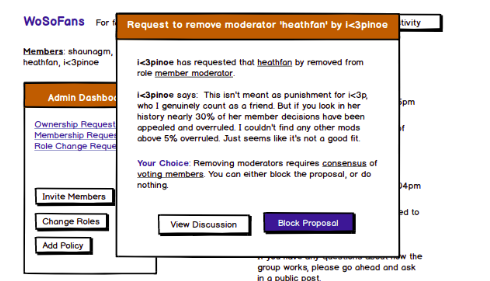

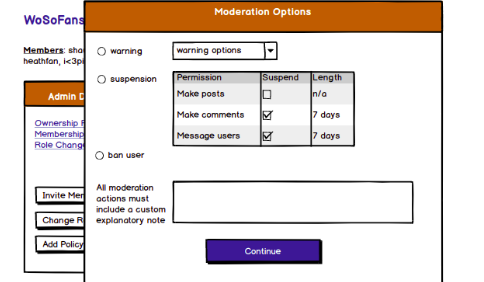

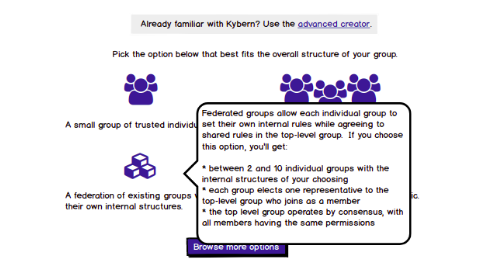

Here are some wireframes for the first prototype I’m building. Its simple purpose is to provide a space for communities of people to talk out and work out their governance structure. Let me briefly walk you through the way this platform allows groups to fit a commons structure.

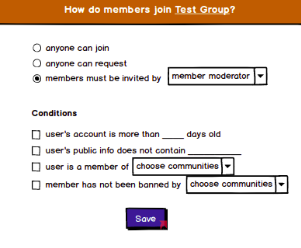

Communities on the platform will be able to be very intentional regarding who is able to join them. They’ll be able to filter out people whose profiles contain slurs, brand new users, or people who’ve been banned by other communities they trust.

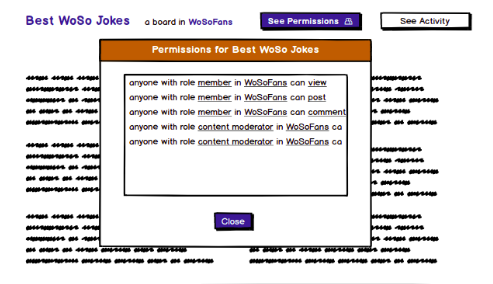

This intentionality is not limited to the boundaries of the community as a whole. Specific resources, like forums or photo albums, which belong to the community can have their own custom sets of rules.

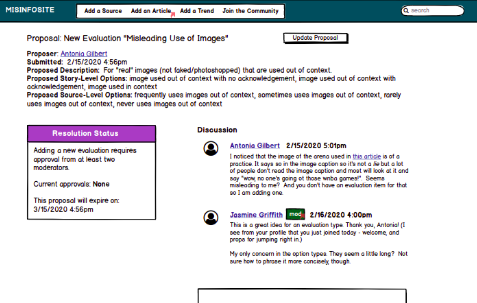

Members of a community will have the ability to suggest changes to the rules that govern the community. Then, through whatever collective decision-making system the community has adopted, the community as a whole will decide whether they want to accept those suggested changes.

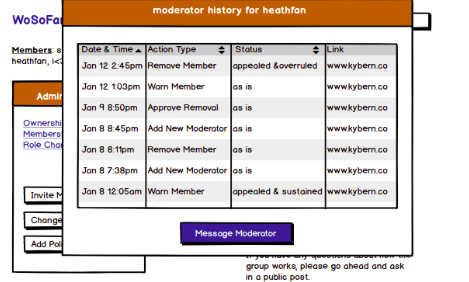

Communities will have the option to make moderator actions completely transparent to the community, so members can see how moderators are using their powers, allowing them to raise issues.

In addition to being able to suggest changes to the rules, members can suggest changes to who is a moderator and what powers they have. So if someone is abusive, or even just ineffective or bad at their job, the community can remove them.

The site expands upon the best practices for graduated sanctions role modeled by Wikipedia.

I’m working to create organizational bylaws for my project that will protect users on the platform from having control of their communities taken from them. Additionally, through the platform itself, communities aren’t forced to rely on an external authority like the platform administrators to address problems like abuse. Instead, they collectively own their groups and can alter their own rules and governance structures to address issues that arise.

Communities on the platform can choose from a variety of template governance structures, which they can then customize to their own needs - or keep as is, if they’re overwhelmed by the options. One of the structures is a “federated” or “nested” group, where one community is made up of many other communities, each with their own customized rule systems.

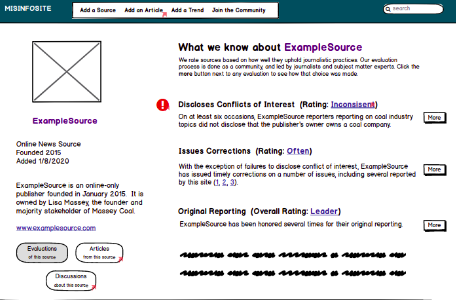

New governance models for domain-specific platforms

The library I’m building can be used to create topic-specific sites as well. For instance, I’m working with some local journalists to build a site that uses commons principles to combat the specific problem of misinformation in the news.

Tools aren’t enough

But of course, tools are useless without a society that understands the concepts that lie beneath them.

The private property model embedded in Facebook and Twitter is so powerful because it is so ubiquitous. It forecloses our minds to different choices we could make, different futures we could build.

One vital thing that all of us can do is learn more about governance. The world is full to bursting with varieties of governance systems for us to learn about - whether it’s the sortition-based democracy of ancient Athens or consensus based models used by Quakers or the many, many forms of governance which are used by communities that have been marginalized by dominant forces in our society. By learning about these systems, we not only open our minds to new possibilities, we also learn to see patterns in what kinds of structures work in which situations. We might learn, for instance, that giving one person a lot of power makes things happen faster but is prone to abuse. We might learn that randomly selecting leaders prevents any one person or group from consolidating power but opens us up to some strange or incompetent leaders.

And we can use this knowledge to improve the communities we interact with - our workplaces and churches and soccer clubs and homeowners associations. Too often I see people talk sadly about a great organization that’s become ineffective or abusive when new leadership took over. By understanding how governance systems work, we can start fixing these organizations.

And with this knowledge, and these strong, robust, healthy smaller groups, we can advocate for larger governance systems like Congress and the Eexcutive Branch and Facebook and Twitter, to make changes, and be more accountable and responsive to the people they’re governing.

Conclusion

There are systems in the world that seem so fundamental that we take them for granted. The model of private property owned by a single person is one of these systems - we just assume this as the default for any organization or process. We often don’t even see it as a design choice we’re making. But it is a choice, and we can choose differently.

Yes, commons can be messy. Democracy can be messy. A whole bunch of diverse people coming to a rough agreement about tolerable behavior can be messy. It’s tempting to look for a simpler and more efficient solution. This is one of the appeals of making new technology. It’s also the great appeal of dictatorships - giving power to someone who’ll cut through all the conflict and the drama and just do what needs to be done.

I see the appeal of dictatorships, but I don’t want to live in one. I don’t want Donald Trump or Mark Zuckerberg or Jeff Bezos telling me how I have to live. And that doesn’t have to be our dystopian future.

People in power want us to be overwhelmed by complexity and uncertainty, so we’ll cede our right to self-determination to them. But we can learn to be patient with complexity and comfortable with uncertainty. They want us to be frustrated with the messiness of democracy and with each other, but we can learn to understand, support, and forgive each other.

They want us to see the problems of, for instance, social media, and say, “These problems are just unsolvable!” And yeah, none of these problems can be 100% solved. But there’s a world of difference between 20% solved and 80% solved - a world of difference. And as they say on the streets, another world is possible.